Sports and Stadium Food: Nationalism and Internationalism

Sören Tollis - March 2025

“They are unique; they are fun; they’re different than any ballpark you’ll find in the States,” claims Mark E. Potts, senior video editor for the Los Angeles Times (Elliott). The mention of “ballpark” lets the reader know that this observation is talking about something sport related. The omitted context further clues the reader in that it’s referring to an aspect of sport differing between Japan and the United States. Jerseys / uniforms? Chants and cheers? Playing style of the athletes? Potts continues, “But quick disclaimer, I didn’t eat any of the fish stuff…They gave me some chopsticks. That was a bad idea. I don’t know how to use chopsticks. Pro tip: You can just stab stuff with them,” (Elliott).

Potts quickly left behind the “fish stuff” and maneuvered towards the American classics offered at the Tokyo Dome baseball stadium – “some french fries and a hot dog, before grabbing a beer,” (Elliott). At this point it’s more than clear that the topic is food, specifically, food offered at sports stadiums.

In “Senses and Emotions in the History of Sport,” historian Barbara Keys illustrates key sensory elements of sporting events—things that impact how people both understand and interact with what they are seeing, including food. Keys sums up this notion well with an example of the infamous boxing match between Jack Dempsey, an American, and George Carpentier, a “French war hero,” (Keys, 23). Keys writes, “The experience of these 90,000 viewers was shaped by their physical encounter with the environment of the arena: its tactility, its smells, and its sounds, including those produced by direct and indirect contact with the other people present, extending in time well beyond the opening and closing bells of the match,” (Keys, 23). A sporting event’s “atmosphere” is made up of all of these things and more – anything at a sporting event that stimulates those in the crowd. The fact that many fans will comment after a game on how fun or insane the atmosphere was reveals how much excitement is associated with sensory elements of sporting events.

Even though the human senses have not biologically changed, the way senses have been utilized in sport has changed over time. Historically, during the age of imperialism in the 19th century, Western powers spread Western sports to the people they colonized as a method of inspiring “disciplining behavior,” – “in part through teaching ‘sonic manners’: when to call, cheer, and applaud, for example. Whistles and bells in games might be considered part of efforts to create a ‘civilized soundscape,’” (Keys, 27). As technological advancements occurred – like radio coverage and live broadcasting on television – and the world continued to undergo globalization, people recognized the massive revenue streams that could be realized from sports. Beyond ticket sales, the in-person experience of going to a sporting event was commodified, creating a “commodified sensory environment” where “preferences for tastes, smells, and sounds are transmitted and changed, not only at the local level but also through national and international networks,” (Keys, 27). In this process of sensory commodification, food features not just as an extra add-on to sports, but rather, an integral aspect of experiencing sports.

Rather than making a click-bait, provocative video like Potts 1, I believe it is more worthwhile (and far more appropriate to this class) to investigate what these foods are, what their implications are, and how they can be connected with broader sports history to reveal insights into Japanese culture and society. By analyzing stadium food in the context of Japanese sports history, I hope to demonstrate how the word “food” can be interchangeable with “sport” as in the following quote from journalist Farah Mohammed for JSTOR Daily: “Any sport is inextricably intertwined with the people, countries, and politics surrounding it…micro-studies in sports could yield profound structural insights if broadened in scope…small-scale athletic culture and phenomena have important underlying statements about our world,” (Mohammed). By focusing on the three most popular sports in Japan: baseball, sumo wrestling, and soccer (Clarke), this paper will show that stadium foods mirror the nationalism and internationalism of contemporary Japan – while upholding Japanese values of high quality, freshness, convenience, and local pride.

To start, I will highlight some Japanese stadium dishes that are commonly mentioned on various stadium websites and food blogs. The ideal empirical strategy for this overview would be some sort of anthropological approach – I myself being on the ground in Japan and visiting stadiums, and observing and ordering off their menus. If done diligently, this would allow for the most thorough analysis of what foods are found in Japanese stadiums, how stadium foods in different regions are prepared differently, and what dishes are only offered in specific regions’ stadiums. Unfortunately, for a plethora of reasons, this approach is not achievable at the time of writing – so I am left to analyze stadium websites and food blogs to gather my “data.”

Examples of Common Japanese Stadium Foods:

Note: The dishes below feature across a variety of Japanese sports stadiums

- Takoyaki: A small, ball-shaped bite of octopus and batter. These balls are typically covered in toppings like pickled ginger, mayonnaise, and seaweed (among others) (“Footie Food…”).

- Bento Box: I will dive deeper into Bento boxes later using Anne Allison’s “Japanese Mother’s and Obentōs: The Lunch-Box as Ideological State Apparatus.” Briefly, though, these boxes have rice alongside vegetables, fish, meat, and “Something a little more extravagant like noodles, fried eel or a helping of sashimi,” (“Footie Food…”).

- Gyudon: A savory and sweet bowl of rice topped with thinly sliced beef and onions, with a wide variety of options for toppings – soft boiled egg, scallions, cheese, etc. (“Footie Food…”).

- Okonomiyaki: A savory wheat-flour pancake filled with cabbage and meat or seafood (zenDine).

- Tonkatsu: A fried pork cutlet – “often served with rice, miso soup, and shredded cabbage,” (zenDine).

- Edamame: healthy, salted soybean pods (zenDine).

- Yakisoba: “fried noodles, meat, cabbage and sometimes a fried egg,” (zenDine).

Immediately, upon reading these menu items, one notices the sheer number of ingredients contained. The amount of ingredients in each dish suggests that the dishes are a bit more complex in comparison to American stadium foods such as: hot dogs, cheeseburgers, chicken fingers, french fries, and other “bread + meat” combinations that can sit under a heat lamp for the duration of a sporting event.

Additionally, the dishes’ relative complexity might suggest to the reader that the food being served is both tastier and of higher quality. In the USA, personal experience tells me that ingredients like seafood and eggs would not be trusted by attendees if offered at American stadiums, though they are mainstays of Japanese stadium foods. Indeed, the variety and perishability of ingredients reveal a central Japanese value when it comes to cuisine: high quality and freshness. As will be explored, Japanese stadium food also provides grounds to examine Japanese values of convenience and local pride.

One counterpart venue to stadiums is the convenience store (konbini) which also demonstrates these very same values, illustrating their prevalence in Japan. Around the world, convenience stores typically carry the same food that is found in countries’ respective sports stadiums. The aforementioned American stadium staple of a hot dog, for example, is a perfect reflection of the “gas station hot dog” in the United States. A scotch pie found in any Premier League stadium in England looks and tastes like a scotch pie found at Greggs – a food chain in the UK (Greggs technically isn’t a convenient store, but it is comparable in the sense that people can grab a quick meal for on the go). This mirroring should not at all be surprising as the need for food in a stadium is often identical to the need for food from a convenience store. In both environments, the consumer wants a quick and easy meal that is portable. Because there is minimal published literature focused on Japanese stadium food, I turn to a significant amount of research (comparatively) focused on Japanese convenience stores, or konbini, as an analogue to arguing for how these dishes encapsulate trends in contemporary Japanese culture.

Across the country, konbini exemplify cleanliness and freshness. In “Shelf Lives and the Labors of Loss,” Gavin Hamilton Whitelaw writes, “Convenience stores are a ubiquitous component of Japan’s neighborhood commercial landscape,” (Whitelaw, 138). In Tokyo alone there is a konbini for every 2,300 people (Whitelaw, 138). Out of the nation’s konbini, the overwhelming majority (75%) of the aggregated sales are from food or drink sales (Whitelaw, 138). American convenience stores have a negative reputation. There is a common worry that the food has been sitting there forever and, because it’s in a convenience store, that it’s super low quality. A common joke is to dub the protein in whatever food you are eating as “mystery meat,” or to question if something like cheese is “real cheese.” These perceptions are likely largely shaped by the environment and atmosphere. A preconceived notion is that, for a lack of better words, the stores are dirty. From personal experience, the bathrooms are, for instance, typically covered in graffiti, the toilets have no back support, the floor is sticky, and the lighting is more often than not hyper-fluorescent yet oddly dim due to cheap, clear plastic covering and some bulb always seemingly in need of being changed. The late Anthony Bourdain, one of America’s most iconic and well-known food personalities, wrote in his memoir, Kitchen Confidential, “I won’t eat in a restaurant with filthy bathrooms. This isn’t a hard call. They let you see the bathrooms. If the restaurants can’t be bothered to replace the puck in the urinal or keep the toilets and floors clean, then just imagine what their refrigeration and workspaces look like,” (Bourdain). I assume most people would agree with this in one way or another…Of course there can be counter-arguments about class and being able to afford the time and products needed to keep a bathroom in tip top shape, but I think it is fair to assume that most people agree with the principle of preferring their food to come from a clean space. Contrastingly, konbini are ultra-clean, appearing practically spotless in Begin Japanology’s “Convenience Stores” episode (even if it is curated view). In fact, further addressing the concerns listed above regarding American convenience stores, “all prepared foods sold in convenience stores are labeled with a production date and consume-by date and time (shohikigen),” and, “By the time many prepared foods reach the store, they often have less than twenty-four hours of shelf life remaining,” (Whitelaw, 139). Whitelaw also writes, “Taste, freshness, safety, and seasonality are critical ingredients for selling food in Japan’s highly competitive and fussy consumer market and convenience store companies pay considerable attention to product freshness and appearance,” (Whitelaw, 139). The emphasis on such matters is indicative of Japanese values, culture, and the intensely competitive konbini marketplace; there is a certain standard that must be met when it comes to food.

Japanese stadium food follows these same principles. zenDine, a writer for the open publishing platform Medium who lives in Japan and regularly attends the country’s sporting events, writes, “One thing that sets Japanese stadium food apart is the unique food culture that surrounds it. From street stalls to gourmet vendors, stadium-goers can find a wide range of delicious and enticing food options…In addition to the variety of food options, the service and quality of the food are also noteworthy. The vendors take pride in offering fresh, hot, and delicious food to their customers,” (zenDine). Abiding by the principles that one would expect of a restaurant – of using fresh and high-quality ingredients for dishes, for example – at a sports stadium, the dishes illustrate a key value of Japanese culture: order. There is a correct way for things to be.

This quality is further illustrated by the bento box, which, as mentioned, is a staple in Japanese stadiums. Returning to the aforementioned article from Anne Allison, I highlight order and discipline as Japanese traits. Allison details principles in which Japanese food is “customarily prepared: perfection, labor, small distinguishable parts, opposing segments, beauty, and the stamp of nature,” (Allison, 198). She adds, “there is an order to the food: a right way to do things, with everything in its place and each place coordinated with every other,” a “rule” which reaffirms social order. The order illustrated through food is reflected in fan behavior as well. In America “slaloming around sticky soda spills, toppled bags of popcorn and mini mountains of peanut shells is often accepted as part of the normal sports stadium experience,” (Keh). This contrasts sharply from Japanese stadiums as “[in Japan] tidiness, particularly in public spaces, is widely accepted as a virtue,” demonstrated by Japanese fans at the 2022 FIFA World Cup “meticulously cleaning the stands at Ahmad bin Ali Stadium, picking up trash scattered across the rows of seats around them,” and garnishing worldwide praise in doing so (Keh). Even though not all Japanese people or Japanese dishes are orderly, there’s certainly a cultural value associated with cleanliness and order.

Another value in Japanese society is convenience. In Begin Japanology’s “Vending Machines” episode, it is shown how Japan has mass amounts of vending machines offering virtually everything food or drink related (as well as non-eating/drinking products) around every corner, and, as mentioned, konbini are everywhere – even with the same konbini having multiple locations in close proximity (though this is typically for strategic management purposes). In the same fashion of having things conveniently available, in Japanese sports stadiums, “there’s an emphasis on hospitality, making the game the center of attention, so fans don’t have to get up to refill their drinks,” as “women wearing tank backpacks filled with beer and soda” can be seen “Running up and down the stairs of the stadium,” (Pulgar). The desire for convenience is correlated with rapid economic growth following World War II and the development of consumer culture that came with that – the post WWII period will be addressed more when analyzing sports history more directly later on.

In her article, Allison concludes, “At one level, food is just food in Japan-the medium by which humans sustain their nature and health. Yet under and through this code of pragmatics, Japanese cuisine carries other meanings that…are mythological. One of these is national identity: food being appropriated as a sign of the culture. To be Japanese is to eat Japanese food,” (Allison, 198). The latter part of this conclusion brings us to another value that can be drawn from Japanese stadium foods – emphasis on localness, something we will soon connect to Japan’s sports history. Like konbini and vending machines in Japan, different regions in Japan see their stadiums offer dishes respectively local to them. Though bento boxes are available at nearly every Japanese stadium, “each [stadium] [still] celebrates the specialty of its region” through the ingredients used, as “so many teams have tie-ups with local…food suppliers,” (Hamaker) (“Footie Food…”).

The importance of local food to Japanese national identity is strong despite, as of 2010, the fact that 61% of food consumed in Japan was imported – with the reason found in historical context (Rath, 146). During WWII, “shortages…shipping blockades, and the reallocation of food resources for military use” saw the Japanese government promote a diet of “local,” easy-to-obtain foods – “coarse grains, rustic ingredients and folk recipes,” (Rath, 147). The majority of Japan’s population found the diet unappetizing. Following the war, with its recovery, Japan experienced a transition from “food to cuisine…towards more diverse and luxurious sources of food energy such as meat dishes, as consumers have sought to make daily dining a more varied and pleasurable experience,” (Rath, 158). While this quote is referring to increased meat consumption in the Japanese diet, post-war food shortages and economic turmoil led to major changes in the general Japanese culinary landscape. Beyond taste preferences itself, culinary adjustments occurred out of necessity – as can be gathered from analyzing “The Manual of Home Cuisine” from The Women’s Division of the Green Flag Association (1941) (Sewell, 2014). Coinciding with postwar efforts to generate Japanese pride, the government began promoting local food “as a collection of delicacies and special recipes that together comprised local cuisines and that evoked nostalgia, nature and sustainable agriculture and carried other positive nuances,” – “Local food went from being considered largely uniform, backward, bland, rustic and peripheral to being a panoply of delicacies expressing distinct local cuisines, and was now seen as integral to Japan’s traditional dietary cultures,” (Rath, 147). This shift was catalyzed by the fact that, during the postwar period of economic growth, the masses moving to urban areas “developed new attitudes towards the foods in the countryside that they had left behind,” (Rath, 154). Local foods remain ingrained in Japanese culture and values, from restaurants to konbini to sports stadiums. This is not to say that American stadiums don’t have local dishes – they do; however, it is displayed differently. I recall going to a basketball game in Philadelphia in 2022, and getting a “philly cheesesteak” after seeing it on the menu. While many from Philadelphia seem to be proud for being from the home of this iconic American sandwich, in the stadium, I remember it being significantly more expensive than other items offered while still holding the same low quality of the other items. It seemed to be offered as more of a responsibility, something to check off the list as a “have to” given that the stadium is in Philadelphia – I would be shocked if Philadelphians are proud of having cheesesteaks (poor quality at that) in their sports stadiums. This is different from Japan, where fans seemingly relish having local favorites in their stadiums – knowing that it’ll both be of high quality and fulfill their preferences. After all, in Japan, “despite what is labelled and sold as ‘local’ food to tourists, local food also serves local needs and satisfies local preferences,” (Rath, 218).

Let’s now move to sports history. Sports were used in Japan following WWII to solidify nationalism in the face of global defeat, and, simultaneously, to turn a page in Japanese history and instill internationalism into the population. In the postwar period, ethnicity proved to be an ideal medium of rebuilding a shared feeling of Japanese pride, by emphasizing and constructing a Japanese profile that distinguished them from other groups of people – promoted through sports by the reported resilience and hard work (among other characteristics) of Japanese athletes. In “Japan’s Embrace of Soccer,” William Kelly writes that “ethnicity came to serve such a crucial role as a basis for post-war national identity,” (Kelly, 1238). Kelly illustrates this through Rikidōzan, a sumo wrestler turned professional wrestler, who quickly gained mass popularity across Japan for his fights against American opponents. With televisions now popular postwar, and with a rapidly growing interest in watching sports, Japan watched as “Rikidōzan and his partner endured endless painful dirty tricks and cheap shots from the Americans over and over, until finally, Rikidōzan could stand it no longer and let loose with his most famous move, a so-called karate chop that brought victory (and justice) to the country,” (Kelly, 1238). Kelly writes, “It was Japan versus the USA, Asia versus the West, and Japan, in the body of Rikidōzan, outlasted the brute strength and underhanded tactics of the foreign intruders,” (Kelly, 1238). With such a narrative, it is not difficult to imagine how Japanese people rallied behind Rikidōzan, while perhaps also feeling triumphant and proud by association.

On the “encouraging internationalism” side of things, it is epitomized by Japan’s 1964 Olympics bid. Postwar, “Japanese foreign policy was constrained by the legacies of war and the exigencies of the Cold War,” (Abel, 203). There was little faith in Japan being able to join perceived-to-be beneficial international organizations like the United Nations. Japan recognized the significance international trade would have, but, due to poor relations with countries around the world, could not yet take action on that front. Foreign-affairs experts “turned to ‘soft’ alternatives, such as cultural exchange and popular international events,” (Abel, 204). Hosting the 1964 Olympics inspired internationalism “as the pursuit of national goals by building and strengthening co-operative ties among nations, including private and grass-roots endeavors as well as government-level activities,” (Abel, 204). Internationalists “hoped the Games would also help to increase Japan’s capacity for positive action in the global arena in more concrete ways: by making the entire nation – its people and its physical infrastructure – more ‘international,’” (Abel, 206). This created an alternative, broadened future for the Japanese public that differed from the nationalist agenda sports in Japan also provided – which, as will now be explored, is often fairly closed off to cultural development.

These two Japanese sports narratives can be examined further – and connected to stadium food – through an analysis of, as aforementioned, the most popular sports in Japan: baseball, sumo wrestling, soccer. On sumo wrestling, Kelly writes, “Modern sumo, as it was reorganized in the Meiji period, defined itself as uniquely Japanese, with Shinto trappings and ritual paraphernalia,” (Kelly, 1235-1236). As of 2012, the vast majority of the 620 legitimate sumo wrestlers are Japanese (Kelly, 1240). There is a lengthy “Japanese-coded” process to become one of these wrestlers. Every wrestler lives and trains in one of the 58 stables in Japan, which are essentially living and training quarters. Furthermore, each wrestler must begin first as an apprentice. Kelly describes life in these stables as “from the bottom-up” where “apprentices [must] endure and share the same hierarchical internal relations, the same cloistered and communal dorm living and the same daily training routines,” (Kelly, 1240).

Sumo’s popularity came from its “ability to present itself as both commercialized entertainment and as Shinto-ised national ritual” which also curated a feeling of “prestige” and “patriotism” – which, recalling postwar Japanese objectives, inspired nationalism at a time when a national Japanese identity was under turmoil (Kelly, 1237). Kelly highlights how foreign competitors are often met with criticism and sometimes racism. However, “Some commentators and many fans are of the view that the sport would be in even worse shape without the foreigners,” with many centering Hakuhō’s (a sumo wrestler of Mongolian origin) records and accomplishments in the sport as evidence. Still, sumo wrestling, which Kelly dubs the most “national” of Japan’s sports, as mentioned, sees all competitors go through a strict process to fit the “single ideological standard, whose qualities – physical, psychological and spiritual – are coded as Japanese,” (Kelly, 1240). In other words, foreign competitors are put into this almost Japanese-mold in order to, literally, become a legitimate competitor.

Analogously, the stadium food at sumo wrestling matches, from what can be gathered online, consists solely Japanese dishes. Which, based on the nationalist aspects of the sport, is unsurprising and seemingly fitting. One of the most popular dishes for spectators is chankonabe, a “famous hot pot that sumo wrestlers eat” in their weight gaining efforts (Sakamoto). Another sumo staple is yakitori, grilled chicken skewers, as chicken is a good luck symbol in sumo culture (Japan Journeys)2. It appears incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to find non-Japanese food at these matches – unless you bring your own, which some sumo wrestling venues seem to allow.

This differs from baseball stadiums where, in addition to the popular Japanese stadium staples listed earlier, a wide variety of food can be found; at the Tokyo Dome, for instance, you can find “A beer garden and restaurants serving fare ranging from burgers to ramen to Italian cuisine,” (Hamaker). At the same time, while sumo wrestling perpetuates nationalism, baseball perpetuates globalism. Baseball’s vast stadium food offerings are indicative of the development of an open minded international culture in Japan – which is in accordance with Japan not only trying to build and repair relations with other countries around the world in the postwar period, but trying to get its population to embrace internationalism as well. This latter effort was crucial in the postwar period as Japan, as mentioned, focused on soft forms of diplomacy – requiring the cooperation of its people. However, while of course there are others (like Cuba and the Dominican Republic, which develop a lot of top baseball talents but do not have the same infrastructure – materially or on the corporate side – in their professional leagues as the US and Japan do), Kelly describes the framework of baseball as “binational [between Japan and the US]” and “US-dominated,” (Kelly, 1243-1244). In “Baseball, Besuboru, Yakyu: Comparing the American and Japanese Games,” Keiō university professor Ikei Masaru writes, “The game was brought to Japan in 1873 by the American missionary Horace Wilson, who taught at Kaisei-kō, now Tokyo University. Many of the students whom he taught to love the game subsequently became leaders in government and industry and set the tastes of Westernizing nineteenth century Japan,” (Ikei, 73). Ikei also details how Japan’s interest in baseball grew quickly as people understood it as an American martial art – regarding it “as they regarded kendo (Japanese fencing), judo, and archery,” (Ikei, 74-75). This interpretation of baseball gave the sport spiritual and certain skill implications, making it appealing. Japanese baseball phrases that mean “putting one’s spirit into one throw of the ball” or “washing the soul with a clean hit,” and the general way in which Japan historically interacts with baseball, do not have “equivalents in the way Americans think about or play baseball,” (Ikei, 75). There are also differences in the actual game strategies deployed by Japanese and American teams and coaches – though the technical details are not relevant for this essay.

Postwar, American General Douglas MacArthur encouraged baseball in Japan – practically rejuvenating Japanese interest in baseball by doing so – as he “thought it a properly American sport, appropriate for a new ‘democratic’ Japan,” (Kelly, 1238-1239). However, despite American influence over baseball’s soaring popularity, the Japanese world of baseball aligned with a nationalist agenda. This is exemplified through Wally Yonamine (1925-2011), who, born in Hawaii, became one of Japan’s first baseball stars in the postwar era. Despite his undeniable talent, Yonamine was subject to criticism and dislike from fans and commentators who “found American nisei like Yonamine to be the worst of both sides – neither trusted by fellow Americans nor accepted as Japanese for having been a traitor on the enemy side of the war,” (Kelly, 1238-1239). In fact, Yonamine’s playing career for the Yomiuri Giants was terminated after “the legendary manager, Kawakami Tetsuharu, declared that the Giants would be ‘100% pure Japanese,’” (Kelly, 1238-1239). In the 1980s, the lucrative contracts for ball players from the American league to come play in Japan were also met with frustration by fans and commentators. Kelly points out that around 1,000 foreign players have joined Japanese teams, and over half of them lasted only one season (Kelly, 1239). Taking salaries that far outweigh the standard Japanese ball player’s salary, Kelly describes a “predictable messiah – scapegoat cycle,” where foreign players are “hired and introduced as team saviours, they then meet with mixed success as the season wears on, and are eventually dismissed with loud public criticism of their laziness, selfishness and lack of proper (which is to say, Japanese) fighting spirit,” (Kelly, 1239). The result was a “clear conceptual dichotomy of indigenous versus foreign” that promoted “Japanese ethnic uniqueness and nativism,” further perpetuated by a common practice of Japanese players with foreign origin (like a player born in Japan to parents from elsewhere) being Japanese “in public” – which was accomplished by “insisting that whatever their blood-ethnic backgrounds [were], they [still] all shared the experience of coming up through baseball in the Japanese school system,” (Kelly, 1239). This nativization draws a parallel to athletes going through a Japanese-coded process in order to become a sumo wrestler.

However, the “rigid binaries” of baseball are beginning to “shed some of its ethnic nationalism,” somewhat similar to how more and more people are appreciating the Mongolian Hakuhō’s accomplishments in sumo wrestling (Kelly, 1240-1241). In addition to the rigid binaries “proving to be problematic” over time, Kelly details how this transition was heavily influenced by Bobby Valentine (b. 1950) – a former American ball player who later coached in Japan and won the Asia championship (Kelly, 1240-1241). His success and charismatic personality led to him being embraced by the Japanese public, making the sport in Japan more open to foreign players.

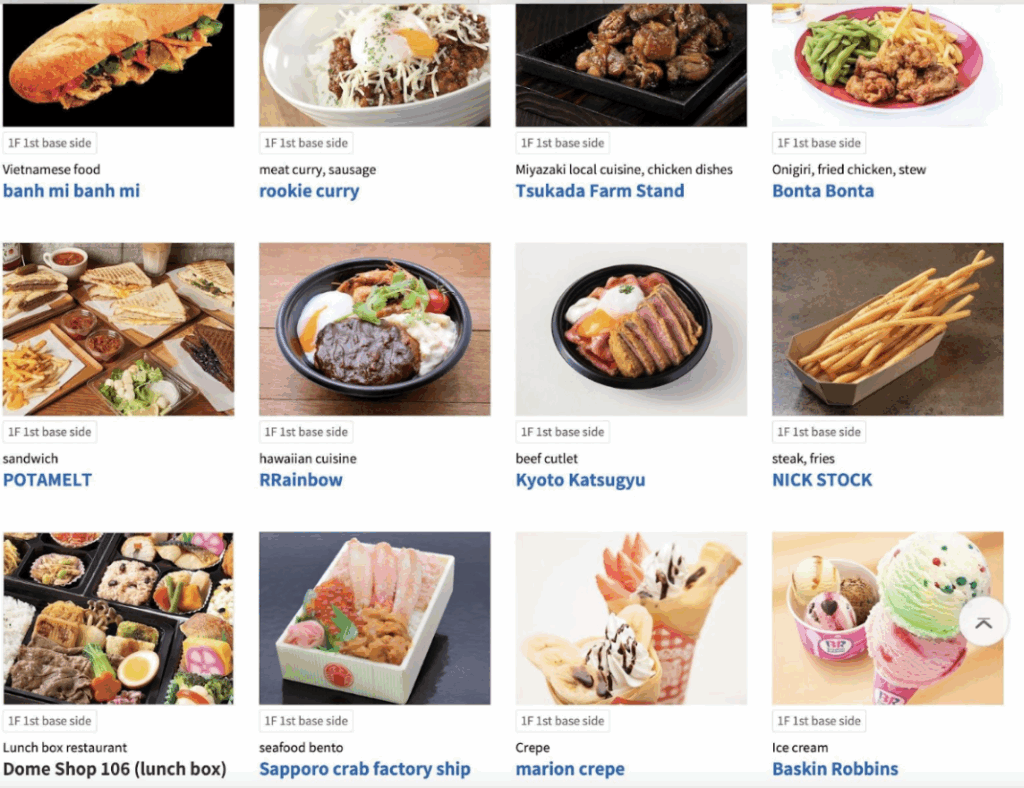

Still, as described, baseball is somewhat limited due to the aforementioned binational framework that exists, consisting of Japan and the US. In other words, internationalism in baseball can only go so far due to the player pool being predominantly from a select handful of countries and its general lack of popularity in most countries around the world. It seems that baseball stadiums offering international cuisines from beyond the US and Japan aim to fill the gap to some degree – in accordance with an evidently increasingly open-minded, cosmopolitan fan base in Japan. In addition to the aforementioned Japanese stadium staples, the Mizuho PayPay Dome FUKUOKA stadium, where the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks baseball team plays, has items like fish and chips, chicken wings, and Spanish charcuterie – as well as an in-stadium KFC and pizza shop. At the Tokyo Dome, where the Yomiuri Giants baseball team plays, fans can get Vietnamese banh mi, crepes, hot dogs, or ice cream from Baskin Robbins in addition to Japanese stadium staples.

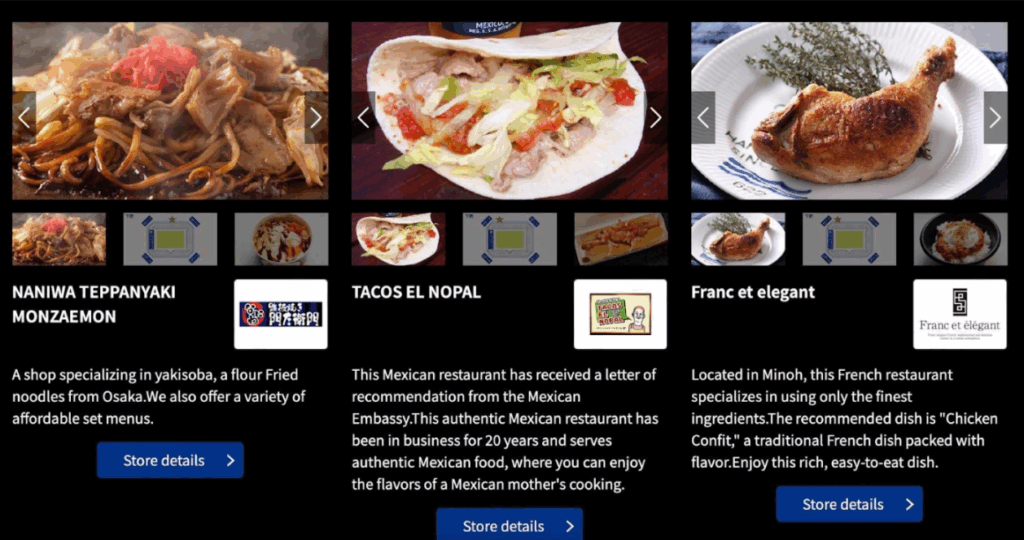

Soccer appears to offer the best of both worlds. Not only do the stadium food offerings encompass a variety of dishes and cuisines like baseball stadiums do, but practically every other aspect – from the players to fan practices – ooze internationalism. Take the Gamba Osaka professional soccer team for instance, who play their matches at the Panasonic Stadium Suita. Their 2025 Player Collaboration menu, which assigns a menu item to each rostered player, features players from Japan, Tunisia, Israel, and Brazil, and dishes like churros and “Mexican hot dogs” alongside takoyaki and bento boxes. The stadium also has an in-house French restaurant, taco shop, and Texas BBQ joint (among other vendors).

Kelly believes that soccer will be Japan’s most popular sport due to its existing international nature – “soccer is broadening the realm of the possible and extending the horizon of expectations,” (Kelly, 1243-1244). While other sports have “been part of the problem for Japan because they have embodied dominant and essentializing images of nationalized ethnicity,” internationalism is a core aspect of soccer – with professional leagues being governed by transnational organizations, like FIFA (Kelly, 1243).

With professional leagues established in every continent aside from Antarctica, the transfer of players from clubs in one country to another is entirely normalized and ingrained in the sport. Japanese players feature in some of the world’s best leagues in Europe, at the same time as foreign players feature across the Japanese professional soccer league, the J.League – and, unlike baseball, many are “signed to regular contracts with little or no special treatment,” while, unlike sumo wrestling, “they are not stripped of their ethnic and racial identities and disciplined into a uniform Japanese mould,” (Kelly, 1241). Kelly even describes how the “global dynamics” of FIFA create playing styles that are always changing, inspired by those of other countries, and interchangeable – epitomized by the Japanese national soccer team having had a “Frenchman, a Brazilian, a Bosnian, a Japanese and…an Italian” as head coaches in recent years (Kelly, 1243).

Another international aspect of Japanese soccer lies in the fan culture. Professional baseball in Japan follows a corporate sports model – where teams are created and owned by companies – as exemplified by the SoftBank professional baseball team in Fukuoka, Japan, operated by the company SoftBank (unsurprisingly). When the J.League was invented in 1993, the league wanted to shift away from this “corporate identity” in order to promote “hometown pride” (and likely to better mirror established professional leagues around the world) before the 2002 FIFA World Cup – which Japan bid to host (a bid which was ultimately successful, with, in international fashion, the tournament being co-hosted by Japan and South Korea) (Copa90, How Football Conquered…).

With a new league and an excitement surrounding it, Japanese fans wanted to display their support but “didn’t really have a frame of reference” so “they looked at what Argentinian and Brazilian fans were doing and they looked at what Italian and English fans were doing and they copied that,” (Copa90, Is The J.League…). The result is fans in the J.League utilizing “Italian and English melodies” in chants, holding banners written in “Argentinian Spanish,” fans of FC Tokyo singing Liverpool FC of England’s iconic anthem – “You’ll Never Walk Alone” – before the game, and fans of Shimizu S-Pulse “doing basically [a] Brazilian samba after they win,” (Copa90, Is The J.League…). In addition to the internationalism of soccer that appeals to many Japanese fans, it is also important to note the appeal that comes with the J.League’s supporter associations that “are more open than those of professional baseball teams” as supposedly 55% of fans at matches are women (Kelly, 1236) (Copa90, Is The J.League…). Aiding this is a far more established professional soccer world that exists for women, where the Japanese women’s national team has found success (Kelly, 1236-1237). Soccer exhibits internationalism through its players and fans, and is reflected in the international food options offered in stadiums.

Reflecting on if “international” foods actually yield internationalization is a critical consideration to end this analysis. As can be derived from the pictures (and as is already evident), many of the international food options are not “authentic.” In this context, I mean that some of the dishes may not be found in a Japanese stadium as they most commonly would be in their respective “origin” country. Some dishes even appear to be created to appeal to an international audience, rather than promoting internationalism itself – like the “Mexican hot dog with lots of salsa” on Gamba Osaka’s 2025 Player Collaboration menu. The intention of this paper is to draw a connection between the agendas promoted by sumo wrestling, baseball, and soccer. Sumo historically promotes nationalism, and remains incredibly Japanese-coded – with matches having menus that are comparatively much smaller to baseball and soccer venues, featuring solely Japanese dishes.

Despite being very nationalistic post-WWII, baseball has opened up to international players and its stadiums offer international food items to fans. However, a bi-national American-dominated framework still exists in baseball in Japan, perhaps putting a limit on how international Japanese baseball can truly become – especially in comparison to soccer. Soccer’s rapid growth in popularity is perpetuated by fandom becoming more international in Japan – not necessarily a change that shifts Japanese fandom away from the nationalism fostered by sumo, but a change that opens up an alternative world of sport in Japan that appears much more open than sports have traditionally been. In this more open sports world, a fan can eat an “Italian” meal at a Japanese baseball game while an American is coaching. Unlike sumo and baseball, soccer’s history in Japan does not have an equivalent nationalistic past. Internationalism is so ingrained in soccer by nature in that it both perpetuates and is perpetuated by a more open sports world in Japan. Simply serving fish and chips at a soccer game does not mean the clientele are international in any deep way, but it is interesting nonetheless that fish and chips can be purchased at a soccer stadium in Japan today, but not at a sumo wrestling stadium and not in Japan pre-WWII and pre-1964 Olympics. Maybe it is just illustrative of capitalism – trying to have more options for people to buy that may be compelling because they seem “exotic.” However, I do not think it is a coincidence that these offerings coincide with an evolving sports culture in Japan. I think these food offerings are made possible because of the internationalism baseball and soccer are spreading – because Japanese soccer games have fans singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” and dancing something similar to a Brazilian Samba. Maybe it does just show a surface curiosity in other cultures and nations, but I still think that is further indicative of a changing sports culture in Japan. Internationalism in sports, especially soccer, may often be more surface level than deep, but it still contrasts with sumo and the traditional agendas associated with sports in Japan.

Sports and food are two domains scarcely touched by academia (though both are growing as areas of focus). As shown, sports and food – primarily because of how prevalent they are in the lives of many in virtually every country around the world – can be studied to reveal historical trends, present day themes, and cultural understandings. I chose to research stadium food in Japan, in particular, due to the complex discourse that can be initiated when combining such rich and typically unknown topics. Sports and food by themselves can illustrate plenty about history and culture, but together give the opportunity to draw connections and comparisons between the two – as I aimed to do in this project.

Works Cited:

Abel, Jessamyn R. “Japan’s Sporting Diplomacy: The 1964 Tokyo Olympiad.” International History Review 34, no. 2 (2012): 203–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2012.626572.

Allison, Anne. “Japanese Mothers and Obentōs: The Lunch-Box as Ideological State Apparatus.” Anthropological Quarterly 64, no. 4 (1991): 195–208. https://doi.org/10.2307/3317212.

Barbaro, Michael. A Shrinking Society in Japan. New York Times. May 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/05/podcasts/the-daily/japan-birthrate-ageing-populati o n.html

Bourdain, Anthony. Kitchen confidential. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Clarke, Andrew. 10 Most Popular Sports in Japan. July 30, 2021. https://www.uniquejapantours.com/10-most-popular-sports-in-japan

Copa90. “How Football Conquered Japan – The Real International Break: Asia.” 2018. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1OFmyFf7wVw&t=1s

Copa90. “Is The J-League The Most Unique League In The World??” 2019. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbwvbkbUfOE

Elliott, Farley. LA Times deletes cringey Tokyo food video from Dodgers game after backlash – SFGATE, March 19, 2025.

https://www.sfgate.com/la/article/la-times-deletes-tokyo-video-20230867.php

Ferguson, Priscilla Parkhurst. “Culinary Nationalism.” Gastronomica 10, no. 1 (2010): 102–9. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2010.10.1.102.

Footie Food at J.League Games!

http://jsoccer.com/new/news/75-j1-news/409-footie-food-linked-ad

Hamaker, Susan. “Chowing Down at Japanese Baseball Stadiums.” The Japanese Food Report. https://www.japanesefoodreport.com/posts/chowing-down-at-japanese-baseball-stadiums

Masaru, Ikei. “Baseball, ‘Besuboru, Yakyu’: Comparing the American and Japanese Games.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 8, no. 1 (2000): 73–79.

Japan Journeys. “What to Eat While Watching Sumo: Kokugikan Yakitori.” 2019. https://japanjourneys.jp/tokyo/attractions/sumo-stadium-food-kokugikan-yakitori

Japanese Stadium Food: 10 Typical Sporting Match Snacks. August 2, 2016.

https://gurunavi.com/en/japanfoodie/2016/08/stadium-food.html

Keh, Andrew. “Cheer, Chant, Clean: Japan Takes Out the Trash, and Others Get the Hint.” New York Times. November 27, 2022.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/27/sports/soccer/japan-fans-clean-up-world-cup.html

Kelly, William W. “Japan’s Embrace of Soccer: Mutable Ethnic Players and Flexible Soccer Citizenship in the New East Asian Sports Order.” International Journal of the History of Sport 30, no. 11 (2013): 1235–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.807557.

Keys, Barbara. “Senses and Emotions in the History of Sport.” Journal of Sport History 40, no. 1

(2013): 21–38. https://doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.40.1.21.

Leitner, Katrin Jumiko. “The Japanese Corporate Sports System: A Unique Style of Sports Promotion.” Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies 2, no. 1 (2011): 27–54. https://doi.org/10.2478/vjeas-2011-0008.

Mohammed, Farah. What sports reveal about society – JSTOR DAILY, October 4, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/what-sports-reveal-about-society/.

Pulgar, Carlota. “A culinary grand slam: ballpark food at Tokyo Dome.” June 13, 2024. https://sjmcjapan.com/tokyo/a-culinary-grand-slam-ballpark-food-at-tokyo-dome/

Rath, Eric C. Japan’s Cuisines : Food, Place and Identity. First edition. London: Reaktion Books, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781780236919.

Sakamoto, Yukari. Sumo 101. January 13, 2016. https://foodsaketokyo.com/2016/01/13/sumo-101/

Sewell, Bill. “Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique , Edited by Michele M. Mason and Helen J. S. Lee.” 2014. Canadian Journal of History 49, no. 1 (2014): 156–57.

https://doi.org/10.3138/cjh.49.1.156.

Whitelaw, Gavin, Kawano, Satsuki, Glenda Susan Roberts, and Susan Orpett Long, eds.

Capturing Contemporary Japan : Differentiation and Uncertainty. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2014.

zenDine. Stadium Bites: What to Eat While Cheering in Japan. Medium. August 12, 2023. https://zendine.medium.com/stadium-bites-what-to-eat-while-cheering-in-japan-de15cc d 39e6b

Footnotes:

[1]: The video has since been pulled down following public backlash. One of my favorite comments mocking the video was: “‘Hey Tokyo Dome has unique foods not found in the US.’ Oh Cool you gonna try them? ‘Nope.’”

[2]: “In a [sumo] match, the winning wrestler remains standing while the defeated falls, touching hand or body to the ground. A chicken is a perpetual winner because it stands on two feet and doesn’t have arms to touch the ground,” (Japan Journeys).