An Anthology on Swiss Rolls

Ian Valenti - Spring 2025

Chapter 1: The History of the Swiss Roll

The Swiss roll is a true marvel of mankind, it encapsulates everything we value as a species within its sponge cake confines, so much so that it has become accepted and integrated into cultures worldwide under differing monikers: the Indonesians call it “bolu gulung,” the Italians call it “caltanissetta,” and Hostess Cakes call them “Ho-Ho’s.” With so many variations and titles, to truly dive into the origin of such a magnificent achievement in culinary history, we need to establish a baseline understanding of what a Swiss roll actually is.

A Swiss roll at its core is a rolled sponge cake with some type of filling, including but not limited to cream, fruit, or jam. The first published recipe we have of a Swiss roll recipe in the USA comes from where all majestic things come from: Utica, New York.[1] In 1852, a journal called the Northern Farmer released a recipe titled “To Make Jelly Cake,” detailing the process of rolling a sponge cake with a jelly filling. [2]

In the United States, the wording used to describe a Swiss roll has evolved over time, what began as a jelly cake turned into a roll jelly cake, a jelly roll, and then somehow, a Swiss roll.[3] One could think this is because the Swiss roll’s true origin, before the publishing of this recipe, was from Switzerland, however, this is not the generally accepted theory amongst historians.[4] While its true place of origin is unknown, the sponge cake is believed to have possibly originated from Slovenia or Austria. The Slovenians have a dish called “potica,” which is essentially brioche dough rolled with walnut filling served on Christian holidays like Easter and Christmas, so this could possibly have played an integral part in Swiss roll’s creation.[5]

Ultimately, while it is unclear where the Swiss roll found its humble beginnings, it has since evolved into a global phenomenon. As mentioned earlier, variations have emerged in countries such as Italy and Indonesia, along with many other countries. Yet, for the focus of this paper, we will be looking at Japan’s take on the roll and the history of Western influences on Japanese sweets as a whole.

Chapter 2: The Western-Japanese Dessert Pipeline

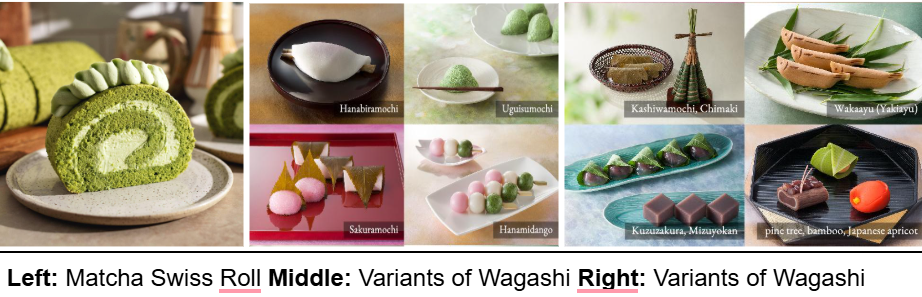

It wasn’t until the 8th Century when Japan was introduced to cane sugar by Chinese traders.[6] Up until that point, the Japanese primarily used honey, fruits, and amazura (a syrup derived from a particular vine) as their means of sweetening.[7] Sugar became especially integral in the production of wagashi, which were sweets commonly served during tea ceremonies.[8] Wagashi is hugely intertwined in Japanese culture, with its origins dating back two-thousand years, when ground up nuts were rolled into what is now known as mochi.[9] That being said, there is no standard definition of what wagashi is, rather, it’s a class of dessert with many types: yokan, rakugan, monaka, mochi, etc.[10]

Over the thousands of years, wagashi evolved and became more refined, these treats were not simply about flavor but also about artistry and sensory experience.[11] Wagashi highlight their natural ingredients, using no dairy and being far less sweet (usually) than their western counterparts.[12] Traditionally such sweets are also consumed with unsweetened tea (either matcha or steeped), which further tends to balance the sweetness. Their ingredients are carefully selected to align with the seasons, reflecting nature and traditional celebrations. They are also predominantly plant-based, making them lighter in comparison to desserts in the West which typically consist of the heavy usage of dairy products, baking, and richer, sweeter ingredients.[13]

Other than the aforementioned Chinese introduction to cane sugar and the initial import of Chinese sweets (karagashi–literally “Tang-dynasty sweets”) from the Nara through the Heian periods, wagashi faced little external developmental influence due to Japan’s Edo-period isolation policy.[14] However, to say wagashi developed entirely in isolation would be imprecise. Prior to the Edo period, Japan experienced substantial influence from Portuguese and Spanish traders in the 16th century, known collectively as the Nanban-jin (“Southern Barbarians”). These European visitors introduced sweets such as konpeitō (sugar candy), kasutera (Castilian sponge cake), and aruheito (a molded candy), all of which became foundational to the evolution of Japanese confections, even though they–like the earlier karagashi and the later yōshoku of the Meiji period–stood distinctly marked by their names as foreign. These Iberian sweets were not only novel in form but also introduced ingredients like refined sugar, eggs, and wheat flour—ingredients that would eventually reshape Japanese tastes and methods.[15] This meant wagashi’s evolution was mostly understood as Japanese and reflected Japanese tastes and the social zeitgeist of what was desirable in a ritual sweet.[16]

The Meiji period in the late 19th century saw the end of the isolationist era and with it brought in a prosperous (and tumultuous) series of exchanges with the outside world.[17] With the introduction of foreign appliances, ingredients, and techniques, the variations of wagashi began to flourish into a multitude of new variations and styles — even including baked wagashi![18]

To bring this paper back to our beloved Swiss roll, it would make sense that it would be somewhere around this time that the Swiss roll made its debut in the freshly globalized archipelago. However, once again, the dessert’s origin breaks any sort of logical thought and was actually believed to come in the 20th century.

The sponge cake’s origin is unclear in regards to its emergence in Japan, however it is generally accepted that it was popularized in the country after World War II. It is hypothesized to have been brought over by the American troops occupying the country after the war concluded.[19] However, one could note that the British had brought Swiss rolls into their territory of Hong Kong during the late 19th century, and Japan’s invasion of Hong Kong could have easily given them the treat.

Similarly to how Japan used foreign influence to innovate their wagashi in the 16th century from Portuguese models, they used their own influence to innovate the foreign recipes brought to them post-Edo era. In our example of the Swiss roll, a common Japanese variant was the creatively named Matcha Swiss Roll.

Matcha, the finely ground green tea powder, did not originate in Japan but became deeply intertwined with Japanese culture through centuries of tradition. Its roots trace back to Tang Dynasty China (7th–10th centuries), where powdered tea was first used.[20] In the 12th century, the Japanese Buddhist monk Eisai, after years of studying Buddhism in China, returned to Japan with both the seeds and the knowledge of preparing powdered green tea in the Zen Buddhist tradition.[21] By planting these seeds, Eisai reaped an ingredient that would become an iconic element of Japanese cuisine for generations to come.[22]

Boasting a slightly bitter yet rich flavor and a vibrant green color, as well as the understanding that it was a “Japanese” ingredient, matcha became an ideal candidate for new variants of wagashi (which some purists may not include as wagashi) that were otherwise strongly inflected by Western ingredients (such as dairy and eggs) and techniques (such as baking).[23] The mastery of the ingredient became a key component in Japanese confectionery, and thus it’s fitting that its flavors were incorporated into foreign desserts such as the Swiss roll to really make the variant of the dessert Japanese.

Chapter 3: Attempting the Impossible

Naturally, after seeing all those images of Swiss rolls and their infinite variants, you must be dying to taste one — or at least know how they taste. So I (and my sous chef Aunt Beth) undertook the gravely intimidating task of baking a matcha Swiss roll for ourselves. We followed a recipe from Just One Cookbook, a website which specializes in Japanese recipes.[24] The first hurdle of many, but quite a large one was: finding matcha in a state that only has a 5% Asian demographic, nevermind a Japanese one.

After traversing from Bridgeport, to Milford, to New Haven in specialized Japanese/Chinese produce stores, every location either was out of stock or didn’t carry the powder. We were starting to think all hope was lost, and then, our glorious savior prevailed: Walmart. After accruing all of the holy ingredients, we began the process of cooking. I won’t go into detail about every step, because ultimately the recipe will do that far more eloquently and beautifully than I do. However, I will go over the major steps and provide photos of the biggest and most insurmountable challenges we faced. Also, for clarification, while some recipes of matcha Swiss roll have normal cream or fruit fillings, we chose to do a matcha cream inside.

After traversing from Bridgeport, to Milford, to New Haven in specialized Japanese/Chinese produce stores, every location either was out of stock or didn’t carry the powder. We were starting to think all hope was lost, and then, our glorious savior prevailed: Walmart. After accruing all of the holy ingredients, we began the process of cooking. I won’t go into detail about every step, because ultimately the recipe will do that far more eloquently and beautifully than I do. However, I will go over the major steps and provide photos of the biggest and most insurmountable challenges we faced. Also, for clarification, while some recipes of matcha Swiss roll have normal cream or fruit fillings, we chose to do a matcha cream inside.

Our first step in the process was creating our matcha flour for the roll. We began by separating egg whites and yolks and then sifting our cake flour and matcha powder together thoroughly, ultimately mixing them all together with some warm milk to provide the green dough you see in the image below. The recipe is like a banshee, it lures you in by seeming super inviting and then on step 5 when you’re too deep to back out it hits you with the worst tidal wave of complex cooking steps you’ve ever encountered. We then had to lay the dough out flat in a sheet pan in preparation to bake it for the first time. I’m really not sure why that lump is there in the photo but we fixed that in post. We then baked the mix for 10 minutes, and then came the first step of death: rolling. We had to roll the cake with parchment paper spiraling between layers to prevent the dough from sticking during baking. This resulted in this chimera of paper and cake mix, that you see to the side.

We then let the log of matcha cool in the fridge for about 30 minutes while we made the cream. The cream itself was relatively simple, you basically just prepared normal whipping cream with some more matcha powder and a tiny amount of sugar. After the cream was prepared and the roll had been cooled, it was time for the second step of death: unrolling. With YouTube comments often citing that this is where things fall apart, we were extraordinarily careful when unrolling our Swiss roll.

Ultimately, we were blessed that it came undone pretty easily, and we lathered on the cream. We then rolled it back up into its log form, wrapped it in parchment paper, and let it cool for about 3 hours. When we took it out of the fridge, the next step was to cut the edges off of the cake to show off the swirling of the cream and make it look nice and neat, and to the right, you’ll see the final product of our hard work. The most important step, obviously, was to taste our invention. The final verdict: personally, I loved the cake and I loved how it tasted. But my Italian-American chef of an aunt did not. I think this is largely due to a couple of factors that will be addressed in the next and final chapter of this anthology.

Chapter 4: Assessing the Differences and Our Thoughts

Ultimately, I think the matcha Swiss roll was a great reflection of Japanese culinary practices, not solely due to the fact that it utilized a traditional Japanese ingredient in matcha, but moreso because it embodied some of the concepts of traditional wagashi despite its Western form. Namely, it’s lack of out and out sweetness.

My aunt kept saying, “God I think this would have been great with some chocolate sauce on it.” Which I think really speaks to the aforementioned differences in ideal dessert flavors between the West and Japan. The recipe only called for roughly half a cup of sugar for a 10-inch roll. This really is reminiscent of the wagashi not boasting large amounts of artificial sweetener in their recipes, rather, emphasizing the natural flavors of their ingredients.

Speaking to the fact that Western palettes/recipes crave more sugar, if you look up “Swiss roll recipe” in Google and just hit the top result, it calls for double the amount of sugar, as well as vanilla extract, chocolate, and cocoa powder (as well as an optional marshmallow creme “fluff”).[25] To make sure this wasn’t a lone variable, I checked the next three top results to see if they followed suit and they all did.[26][27][28]

All this is to say that my aunt may not be alone in her opinion, perhaps the cake would be commonly thought of as not being sweet enough in American households which are used to two times the sugar content topped with marshmallow creme fluff. Regardless, to me the matcha Swiss roll tasted great and was an adventure to make. Through researching its origins a lot of knowledge about Japanese (and world) history can be extracted. But taking it a step further, comparing the Japanese to Western recipes we can see the differences in taste preferences that are present today, as well as a reflection of the dietary customs found in different countries. The subtlety of Japanese flavors in desserts and the everything-to-the-extreme nature of Western desserts are worlds apart, yet, they all get rolled together in this wonderful matcha Swiss creation.

Work Cited

Roll cakes: A delicious history – the old European Restaurant. (n.d.). https://oldeuropean-restaurant.com/roll-cakes/

Jernej Kitchen. (2022, April 19). Potica (slovenian nut roll). https://jernejkitchen.com/recipes/nuts/potica

“The World of Sugar.” Marubeni Shosha 76 (2003): n. pag. Web.

Ashkenazi, Michael, and Jeanne Jacob. The Essence of Japanese Cuisine: An Essay on Food and Culture. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania, 2000.

Wagashi vs. Western Sweets . Sweet Escape Japan. (n.d.). https://sweetescapejapan.com/articles/12

Eva. (2025, March 22). Japanese roll cake, Fluffy Cake Base. Bake. https://bake-street.com/en/japanese-roll-cake-fluffy-cake-base/

Matchaful. (n.d.). The history of matcha. https://www.matchaful.com/pages/the-history-of-matcha

Sous Chef. (n.d.). The sweet world of Japanese confectionery: A deep dive into Japanese sweets. The Bureau of Taste. https://www.souschef.co.uk/blogs/the-bureau-of-taste/the-sweet-world-of-japanese-confectionery-a-deep-dive-into-japanese-sweets

Tachibana, N. (2021, August 20). Matcha Swiss roll. Just One Cookbook. https://www.justonecookbook.com/matcha-swiss-roll/

Quinn, S. (2017, June 1). Chocolate cake roll. Sally’s Baking Addiction. https://sallysbakingaddiction.com/chocolate-cake-roll/

Tang, C. (2022, February 14). Vanilla Swiss roll cake with fudge swirl cream filling. Scientifically Sweet. https://scientificallysweet.com/vanilla-swiss-roll-cake-with-fudge-swirl-cream-filling/

Khan, M. (2021, November 25). Light & moist Swiss roll. Cakes by MK. https://cakesbymk.com/recipe/light-moist-swiss-roll/

Gonzales, J. (2020, August 17). Swiss roll. Preppy Kitchen. https://preppykitchen.com/swiss-roll/

Tokyo Wagashi Association. (n.d.). About Wagashi. Tokyo Wagashi Association. https://www.wagashi.or.jp/japanesesweets-wagashi/en/about/

Rath, Eric C., and Takeshi Watanabe.

“The Power of Japanese Sweets and Sweeteners.” Gastronomica, vol. 23, no. 4, 2023, pp. 1–6. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2023.23.4.1.

Rath, Eric C.

“The Barbarians’ Cookbook.” Japanese Foodways, Past and Present, edited by Stephanie Assmann and Eric C. Rath, University of Illinois Press, 2010, pp. 85–99.

Footnotes

[1] Roll cakes: A delicious history – the old European Restaurant.

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Roll cakes: A delicious history – the old European Restaurant.

[5] Jernej Kitchen.

[6] Shosha 2003.

[7] Ashkenazi, Jacob 2000.

[8] Wagashi vs. Western Sweets . Sweet Escape Japan.

[9] Tokyo Wagashi Association. (n.d.).

[10] Ibid

[11]Sous Chef. (n.d.). The sweet world of Japanese confectionery: A deep dive into Japanese sweets.

[12] Wagashi vs. Western Sweets . Sweet Escape Japan.

[13] Ibid

[14] Wagashi vs. Western Sweets . Sweet Escape Japan.

[15] Rath, Eric C.

[16] Wagashi vs. Western Sweets . Sweet Escape Japan.

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19] Eva 2025

[20] Matchaful. (n.d.). The history of matcha

[21] Ibid

[22] Ibid

[23]Sous Chef. (n.d.). The sweet world of Japanese confectionery: A deep dive into Japanese sweets. The Bureau of Taste.

[24] Tachibana, N. 2021

[25] Quinn, S. 2017

[26] Tang, C. 2022

[27] Khan, M. 2021

[28] Gonzales, J. 2020