A Creative Exploration of Saké

Oscar Rabatin - March 2025

What is saké (酒)?

In Japanese, the characters “日本酒” are pronounced as ‘nihonshu’ and translate to “Japanese alcohol” in English. These characters contain the third character “酒” which can be pronounced as ‘saké’ and which on its own can translate in English to both “alcohol” as well as “rice wine”. These semantics reflect the ubiquity of the specific alcoholic beverage that is saké, a wine made from rice, within the broader landscape of alcoholic beverages in Japan. Indeed, for much of premodern Japanese history, rice wine was the only available alcoholic beverage, except for some regional cases such as shochu (distilled alcohol from sweet potatoes, found particularly in southern climates such as Kyūshū), red wine in Yamanashi prefecture, and awamori in Okinawa. So what then constitutes saké? Essentially, saké is a beverage made from four primary ingredients: water, rice, yeast and kōji. While this recipe is simple, there are important particulars to saké production which define the drink and complicate its history just as the particulars of grape cultivation complicate western wines.

The process of saké fermentation, turning water to wine so to speak, is dependent on a basic chemical interaction between the rice, yeast, and kōji. To clarify a potentially unfamiliar term, “kōji” is the Japanese word for a specific kind of mold (Aspergillus oryzae) which is critical for saké production. As I will explain later, saké rice is characteristically rich in starch (unlike grapes that are already glucose) and during the fermentation process the starches within the rice are converted into sugars by the enzymes produced by kōji. Kōji spores produce amylase, protease, and various other enzymes which serve to saccharify (deconstruct) the complex carbohydrate structures of the rice starch into the simple sugar glucose (Rath, 42). It is this glucose that can then be converted into ethanol by the yeast during fermentation which in turn makes the saké alcoholic. While there are other components of saké production like the incorporation of an acid to reduce unwanted bacterial growth and the addition of distilled alcohol (which some consider to be shortcuts or antithetical to the tradition), this basic process involving water, rice, yeast, and kōji is responsible for the essence of the beverage.

Unsurprisingly, the most important ingredient in saké production is the rice. There are a vast number of strains and characteristics which differentiate types of rice in Japanese cuisine and saké production and it is the type of rice used to make the wine which primarily determines the quality of a given saké. Generally, Japanese rice can be divided into two broad categories, non-glutinous and glutinous rice. Counterintuitively, this distinction does not refer to the gluten content in these respective rice types but instead their amylose content. Amylose is a type of starch which gives rice its firmness when cooked. Glutinous rice is typically short grained, low in amylose, and sticky when cooked whereas non-glutinous rice is typically long grained, high in amylose, and firm when cooked. While both of these types of rice can be used to make saké, it is specific varieties of non-glutinous rice which have been cultivated over generations to complement the production of saké while glutinous rice varieties are more commonly used for cooking (namely as mirin, a type of sweet sake).

A brief history of saké

The Japanese history of brewing alcohol with rice is rich and rivals those of other ancient beverages such as grape wine and wheat beer. The origins of rice-based alcohol brewing dates back to the late Jomon-early Yayoi period, circa 500 BCE, with the spread of rice agriculture from mainland China into Japan (Francks, 153). It was likely not long after rice was introduced to Japan that it began being used to ferment alcohol. The first written account of saké consumption in Japan exists in the Book of Wei which is a Chinese historical text written during the Asuka period, circa 550 AD (Wikipedia). A popular myth that surrounds early saké brewing in Japan is that it was fermented from rice that was chewed and spit out of the mouths of young, virgin women whose saliva was rumored to be more concentrated with the necessary enzymes for saccharification. This traditional type of saké is known as “kuchikamizake” (“mouth chewed saké”) and is thought to have been brewed in rural areas, particular the Okinawa prefecture, in order to be used for special religious ceremonies (Rath, 42). Contemporary saké consumption carries the legacy of this myth with gendered and sexualized language common in the brand names of modern saké as well as its modern reputation as an “old man’s drink” (Rath, 42).

The anonymously written text titled Goshu no nikki, which translates to Saké Journal in English, is a medieval account of saké brewing techniques which dates to 1566 AD but is suspected to have been originally written as early as 1355 AD. Saké Journal is considered a “secret text” which recorded coveted oral traditions of saké brewing passed down from religious authorities to master brewers (“Toji”). Before the existence of secret texts, the craft of saké brewing was dictated by trial-and-error and the essential knowledge acquired by this process was confidentially exchanged orally within sects of Toji (Rath, 43). Even in the written record of Saké Journal in which oral traditions were put to paper, there is mention of further “oral secrets” which were omitted and reflect the interest of the writers in restricting the dissemination of their most treasured techniques. The secrecy that envelops saké brewing at this time reflects both the artisanal nature of the craft (that resulted in an intoxicating, magical substance) as well as its budding reputation as a commercial product for which there were valuable trade secrets (Rath, 44).

While prior to the 14th century, saké was reserved for nobility and religious ceremony in Japan, during the late Kamakura-early Muromachi period, commercial production of saké began in the countryside for sale and consumption at local markets and other public events (Francks, 153). During the Tokugawa period, both the trends home-brewing of unrefined saké (“doburoku”) as well as mass public saké consumption on special occasions grew in popularity. Economic growth in Japan in the 17th and 18th centuries correlated with a significant rise in saké consumption as breweries became more common, saké-drinking culture became less ceremonial, and the drink became more accessible for the upper-middle class (Francks, 156). With industrialization and urbanization in the 19th and 20th centuries, incomes rose and modern working class drinking culture developed making the consumption of saké, along with western beer, significantly more commonplace. World War II with its rice shortages was a dark period of sake production, and unfortunately the shortcuts taken as accommodations haunted cheaper sake even after the war (Oishinbo: Sake). With post-war recovery and increased incomes, as the consumer demand for saké grew in Japan, the interest in product differentiation inspired the emergence of “craft” breweries such as the Tedorigawa Brewery. As depicted in the 2015 documentary “The Birth of Saké”, the Tedorigawa Brewery, founded in 1870, is a small family-owned brewery in Ishikawa Prefecture which today competes within a highly competitive industry by implementing traditional brewing techniques dependent on assiduous labor and the masterful instincts of its Toji (Shirai).

Grading saké rice and saké

For most saké, non-glutinous saké rice varieties are cultivated and prepared in order to produce specific flavors of varying quality (or more precisely, dryness, with drier varieties currently generally enjoying higher status). The characteristics of saké rice which make it best suited for the fermentation process include: long grain length, high grain strength, low fat content, low protein content, and high starch content (Taguchi). When saké rice is prepared for fermentation in the Japanese breweries known as sakagura (酒蔵), the rice is milled down in order polish away the exterior bran of the grains and expose the starchy white core of the grain known as the shinpaku (心白 “white essence”). As it is the starch which the kōji needs to feed on during fermentation, by exposing the shinpaku and removing the fats and proteins through milling, the resulting saké has a comparatively cleaner and higher quality taste.

Beyond the genetics of the saké rice, the extent to which the rice that is used to brew is milled down from its natural form is the standardized metric for grading saké quality. The grading scale ranges from futsūshu which are “regular,” low-grade saké to daiginjo and junmai daiginjo which are considered the most premium types of saké. Futsūshu have mill rates, or seimaibuai, of 70% and above (meaning 70% or more of the rice is preserved) whereas daiginjo and junmai Daiginjo have mill rates of 50% and below. Mill rate refers to the percentage of the rice grain which is removed due to milling before the fermentation of a saké, and generally speaking, the lower the mill rate, the more premium the saké. The term junmai (“pure rice”) specifies that no distilled alcohol has been added during the brewing process, so, as a rule of thumb, all sake types containing Junmai in their name have been made from only water, rice, kōji, and yeast (Taguchi).

My attempt at home-brewing saké (酒)

In order to further my understanding of the iconic Japanese drink that is saké, I decided to try my hand at home-brewing my own batch here at Wesleyan University. This process has taken approximately 5 weeks and involved much trial and error but has ultimately been quite rewarding as you will come to find out as I explain my progress.

When I took to the internet to begin researching how I would go about making my own batch of saké, I quickly discovered that youtube and reddit would be invaluable resources for me. As you might be able to guess, there are lively home-brewing communities on both of these social media platforms and plenty of quite accessible information on the subject of home-brewing saké specifically. While much of the instruction that one can find on youtube and reddit lacks academic rigor, considering this was not only my first time making saké but my first time home-brewing any alcohol, I figured that following the advice of experienced home-brewers would give me the best chance of producing something that resembles saké, if even remotely. Ultimately, throughout this process the resource that I referred to most regularly for practical instruction as well as measurements was a youtube video published by the “TheBruSho” channel.

Inoculating kome-kōji (米麹)

At the start of this 5-week process, I made the decision to try making my batch of saké using kōji mold which I would grow myself; in retrospect, this decision was a bit ambitious but still one that I’m glad to have made. When making saké, it is not simply kōji mold spores that are added to the water, yeast, and rice, but it is instead a separate batch of rice that has been steamed and inoculated with the kōji spores which is added. This kōji-inoculated rice is known as kome-kōji (“kōji rice”). Essentially this means that before I fermented the alcohol (saké), I attempted a fermentation process in which I moderated the conditions of a “starter” batch of rice along with kōji spores in order for the spores to colonize the “starter” rice that would feed the saké.

At this point it is important to make note of the type of rice that I used in my attempts to make both kome-kōji and saké. Despite glutinous, unpolished rice being unconventional and arguably sacrilegious to saké brewing, on account of my limited budget for this project and reassurances from home-brewers on the internet, I used mochigome for this project. Mochigome is a short-grained, sweet rice that is commonly used to make mochi and is far from ideal for saké (but is used to make mirin, which is a sweeter alcohol used primarily for cooking).

That said, let me remind the reader of the Zen philosophy of Zen Master Dōgen who in the 13th century wrote: “Your attitude towards things should not be contingent upon their quality… A dish is not necessarily superior because you have prepared it with choice ingredients, nor is a soup inferior because you have made it with ordinary greens” (Dōgen, 7, 13). While using mochigome to make saké is akin to using ordinary greens to make soup, it is viable nonetheless and allows for an exercise in judging a product without necessarily judging its quality. Besides, even were I to have used glutinous rice, I didn’t have the equipment to polish the rice, so making “high-quality” saké would have been impossible.

Back to the kōme-koji: I began my batch by steaming the mochigome. Steaming is a critical step in kōme-koji and saké production as it allows you to achieve a consistent cooking in which the starches in the shinpaku are softened and the grains are properly moistened without becoming sticky. Before steaming, I soaked the 400 grams of mochigome that I would use in a cold water bath for 1 hour in order to hydrate the grains and begin removing the detritus from their exteriors. After the 1 hour bath, I rinsed the rice under cold running water 6 times until the water passing through the grains ran clear indicating that they were clean. Next, I let the rice air-dry for 20 minutes so that it wouldn’t be excessively wet when steamed. Once the rice was dry, I steamed it for 40 minutes, stirring it every 10 minutes to ensure an even cook. As I don’t have a rice cooker, when steaming rice here and later on, I used a jerry-rigged steamer that consisted of a large pot with a few inches of water at the bottom and a strainer propped up above the boiling water for the rice to sit in. All of these components were thoroughly sterilized. Below is a picture of my steamer:

This steamer worked surprisingly well and after 40 minutes, the rice was fully cooked through and ready for fermentation.

In order to ferment kōme-koji, you must mix the koji spores into the steamed rice and then leave the mixture in a temperature controlled environment for 30 hours. The fermentation environment must be damp and, most importantly, warm in order to facilitate the growth of the koji colony throughout the rice. In order to successfully inoculate the rice, the koji spores must be kept between approximately 82°F and 97°F. If the temperature is lower than 82°F, the mold will grow slower and the risk of unintended harmful bacteria growth increases. On the other hand, if the temperature is higher than 97°F, the heat-sensitive koji spores could be killed. In order to create this climate-controlled environment for my kōme-koji fermentation, I made a simple incubator with a 21 x 15 x 16 inch cardboard box and a light bulb fitted to the interior wall of the box as a heat source. The light bulb that I used was a 75 watt LED light bulb and I assumed that it would be powerful enough to maintain the incubator’s temperature which in retrospect, was a problematic assumption. Below is a picture of my incubator:

To prepare my 400 grams of steamed rice for the kōme-koji fermentation I placed the rice into a sterilized aluminum casserole pan and sprinkled it with approximately 2 grams of koji spores that I ordered online. I then mixed the steamed rice with the spores using a sterilized spatula to ensure that the rice was evenly coated. To create the necessary damp environment for the fermentation I covered the layer of koji coated rice with a small towel that was damp with warm water. Next, I placed a temperature probe under the towel sticking into the rice, placed the pan into my incubator, sealed the incubator, and left the rice to ferment for 30 hours.

Every 7-10 hours I would open the incubator, mix the rice with a spatula, re-dampen the towel with warm water, give the rice a smell, and check the temperature. I soon realized the limits of my incubator as the temperature of the rice maintained an average temperature of 74°F, never exceeding 78°F. As a result of the low temperature, the koji growth was slow. By hour 30, when the rice should have been fully inoculated, there were still no obvious signs of inoculation except for a faint sweet smell coming from the rice. I left the rice to incubate for an additional 14 hours and it was after doing so that I was able to see recognizable growth. The sweet smell became stronger and there was both white and yellow mold growth visible on the surface of the rice. Below are pictures of the kōme-koji after the 44 hours of incubation:

As I was aware of the greater risk that unsafe bacteria would grow on the rice given the low temperature of the incubator and the longer incubation time, after seeing the yellow mold, I suspected that the kōme-koji might be contaminated. While there was also likely healthy koji growth, considering this kōme-koji would dictate the fermentation and flavor of the saké, I didn’t want to take the chance of spoiling the batch with unknown bacteria. Although I decided to abandon my homemade kōme-koji, in making it I gained a significant appreciation for the process with its nuances and unpredictability.

The saké fermentation

As I chose not to use my homemade kome-koji, in order to begin the fermentation of my saké I ordered pre-inoculated dry koji-kōme online. I also acquired a 1 gallon “fermenter”, citric acid, and EC-1118 wine yeast. The fermenter consisted of a 1 gallon glass bottle with a rubber cork. The cork featured a plastic airlock which is filled with water to prevent outside air from entering the bottle while allowing the carbon dioxide produced by the fermentation to exit. In modern saké fermentation the incorporation of a neutral acid such as citric acid or lactic acid has become common practice in order to combat the growth of harmful bacteria during fermentation (Rath, 42). The EC-1118 wine yeast is a dry wine yeast that is popular for making a variety of wines and while it is not specifically saké yeast, it was accessible and would suffice as a substitute.

Roughly following the recipe used by “TheBruSho”, for my saké I again soaked, washed, dried, and steamed 750 grams of mochigome just like I had before for the kōme-koji. After the rice was steamed, I spread it out on a baking pan and allowed it to cool down to 80°F. Once cooled, I funneled the mochigome into the sanitized fermenter along with 200 grams of pre-inoculated kōme-koji, 2.5 grams of citric acid, 3 grams of the EC-1118 yeast, and lastly, 0.5 gallons of distilled water. After combining all the ingredients in the bottle, I gave the mixture a thorough stir, sealed the airlock, and set the fermenter in the dark and cool corner of my closet. The fermentation process had now begun and now all I could really do was hurry up and wait. For the first week of the three-week ferment, I opened the fermenter daily and gave the saké a stir in order to allow for the koji to spread throughout the rice. Almost immediately there was obvious chemical activity within the fermenter as the carbon dioxide produced by the fermentation began bubbling up from the rice to the surface of the liquid. This was a very reassuring sign. After the first week of fermentation, the two-week long Wesleyan spring break began so because I was leaving campus I left the fermenter in my closet to finish the ferment. I returned to campus for one day during the first week of break (second week of the ferment) and checked in on the saké. At this point there continued to be bubbling, the rice had broken down significantly, and the liquid had gained a slight yellow hue. The most significant change was the smell. At this point there was a distinct smell of ethanol coming from the opening of the bottle which was another reassuring sign.

After the three week fermentation was complete, I was eager to see the state of the saké. In the final week of fermentation the rice had further broken down, the yellow hue had deepened, and the bubbling had slowed. Before tasting the saké, I removed it from the fermenter, filtered it through a cheesecloth and strainer, and then bottled it. Below are pictures of the finished saké in the fermenter and squeezing the saké out of the residual rice in the cheesecloth:

Once the saké was bottled, I tasted it for the first time and was chiefly surprised by the seemingly high alcohol content in the taste. I’m unsure of the exact alcohol by volume as the chemistry of the measuring process is beyond me but saké is generally between 10% and 20% alcohol and my batch seems to be closer to 20%. While its flavors are not particularly complex, the saké has a dryness to it which makes it easy to sip. There are some very subtle smokey and earthy notes as well as a sweetness which I believe comes from the mochigome. All in all, while I may not have made top-shelf saké, or even bottom-shelf saké for that matter, I did make saké nonetheless which in itself is satisfying. Yet again, the philosophy of Dōgen rings true.

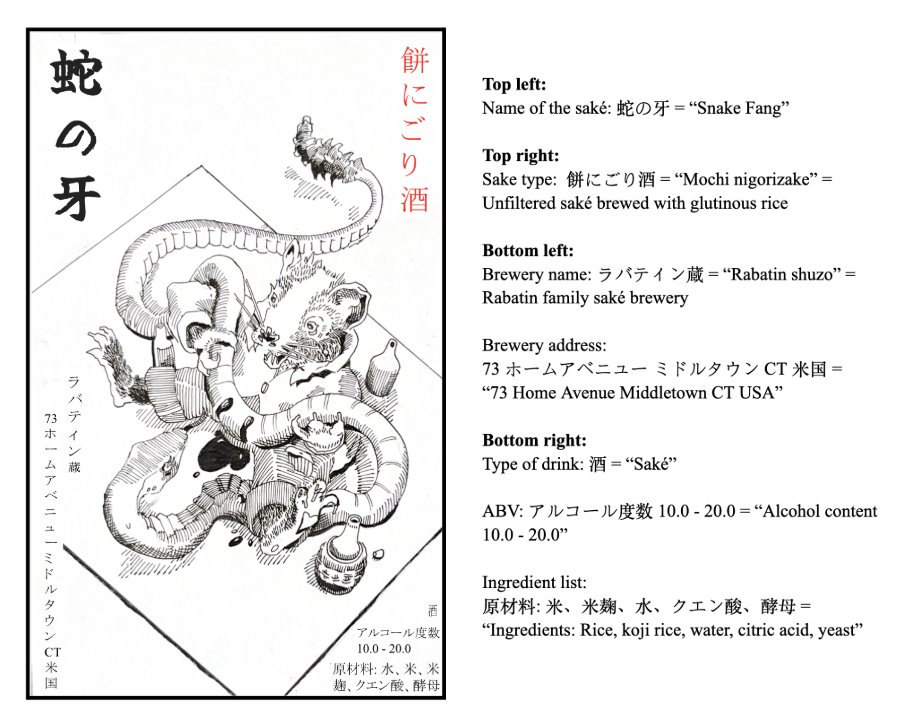

To further explore the production of saké I decided to make a label to mark my bottled saké following the conventions of saké labeling as outlined by “Saké-Talk.com”. I asked my artistically talented brother, Simon Rabatin, to design an illustration for the label and I used Google Translate to find Japanese characters to convey the important information describing the saké. After consulting Prof. Watanabe, I determined that the most poetically appropriate name for the saké would be “蛇の牙” or “Snake-Fang” saké. Below are pictures of the label we produced, a key for the translations to English, and my first meal accompanied by Snake-Fang saké which was mediocre salmon sushi from Wesshop:

Reflections

Reflecting on this process, I feel simultaneously satisfied with my effort in making this saké and encouraged to improve upon it in the future. Now that I have had this experience and understand the basics of this craft, I would like to further explore the flavors of modern Japanese saké and refine my technique by brewing more batches. Through this project I’ve come to appreciate the intricacies of producing such a seemingly simple drink and the historical significance of artisanal trial-and-error to saké brewing has resonated significantly with me. I’m fascinated by the perceptual acuity that brewing a good batch of saké demands and I think that home-brewing saké in pursuit of that good batch could become a gratifying hobby of mine.

References

Dōgen. How to Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment. Translated by Thomas Wright, Shambhala Publications, 2005.

Francks, Penelope. “Inconspicuous Consumption: Sake, Beer, and the Birth of the Consumer in Japan.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 68, no. 1, 2009, pp. 135–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20619677 . Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Rath, Eric C. “Sake Journal (Goshu No Nikki): Japan’s Oldest Guide to Brewing.” Gastronomica, vol. 21, no. 4, 2021, pp. 42–50. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27240163 . Accessed 18 Feb. 2025.

Shirai, Erik. “The Birth of Saké” Documentary (2015). https://www.birthofsake.com/

Taguchi, Tadaomi. “What Is Good Rice for Sake Brewing?” SAKE Street, 13 Nov. 2024, sakestreet.com/en/media/characteristics-of-rice-for-brewing-sake#quality-classification-system .

TheBruSho. “How to Easily Make Sake at Home.” YouTube, YouTube, 6 June 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=A3ep5XGdV9I&t=502s.

Wikipedia. “Saké.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Mar. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sake#:~:text=The%20origin%20of%20sake%20is,sake%20brewing%20was%20Aspergillus%20oryzae.